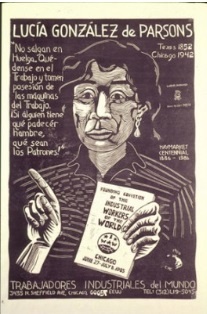

Lucy Parsons

This Lucy Parsons biography was originally published in the When Angels Fly book blog, on March 2024.

“What I want is for every dirty, lousy tramp to arm himself with a revolver or knife on the steps of the palaces of the rich and stab or shoot their owners as they come out.”

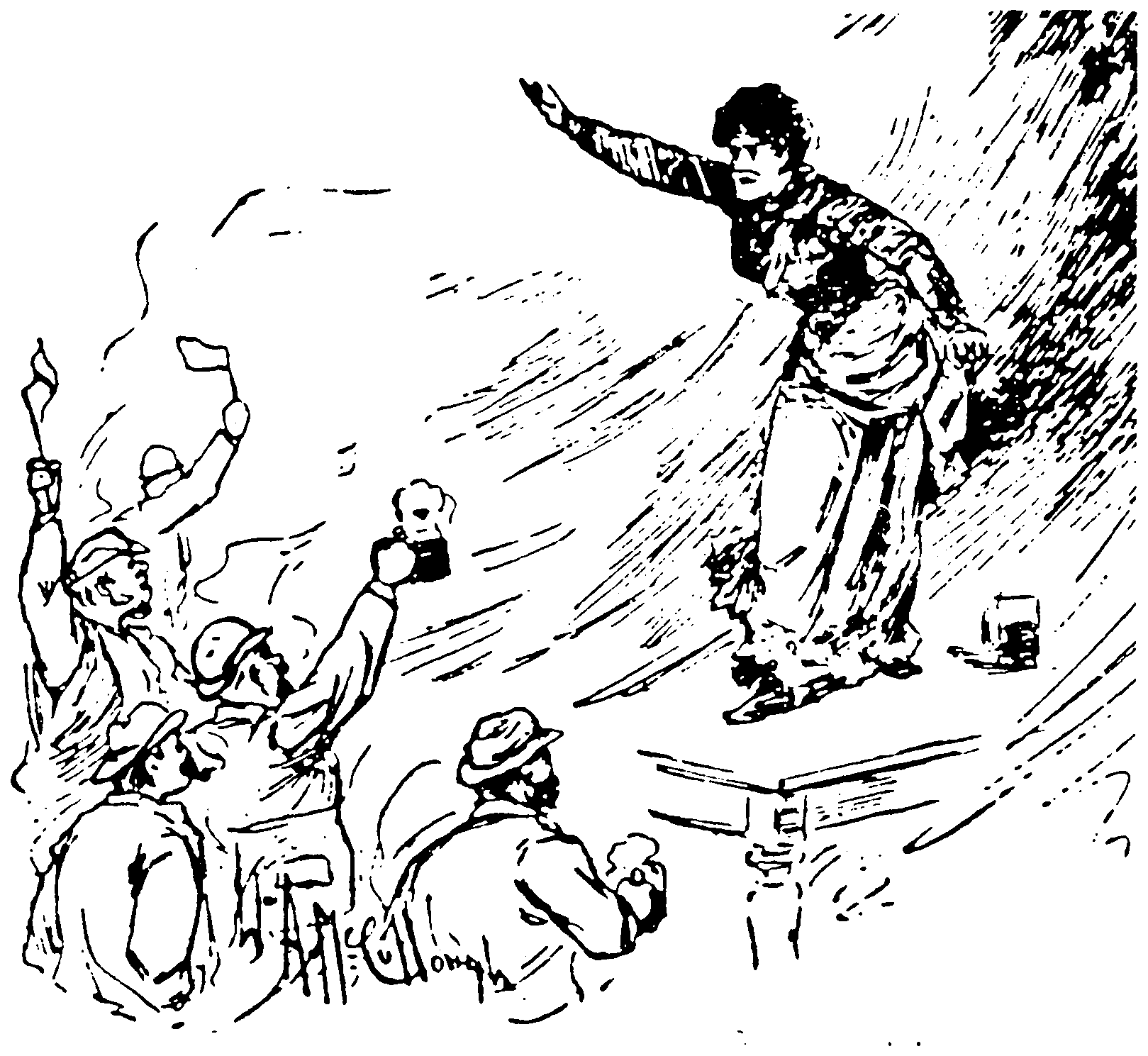

This was what Lucy Parsons, then in her 80’s, told a crowd at a May Day rally in Chicago, at the height of the Great Depression. The way folk singer Utah Phillips tells the story, she was the image of everybody’s grandmother, prim and proper, face creased with age, tiny voice, hair tied back in a bun.

Fascinating woman? Absolutely. But what does she have to do with historical fiction?

Lucy’s Early Life

Little is known about Lucy Parson’s early life, but various records indicate that she was born to an enslaved African American woman, in Virginia, sometime around 1848-1851. She may also have had indigenous and Mexican ancestry. Some documents record her name as Lucia Gonzalez. In 1863, her family moved to Waco, Texas. There, as a teenager, she married a freedman named Oliver Benton. But she later married Albert Parsons, a former Confederate officer from Waco, who had become a radical Republican after the war. He worked for the Waco Spectator, which criticized the Klan and demanded sociopolitical equality for African Americans. Vigilantes shot Albert in the leg and threatened to lynch him for helping African Americans register to vote. It is unclear whether her initial marriage was ever dissolved, and likely that her second marriage was more of a common-law arrangement, considering the anti-miscegenation laws that existed then.

In 1873, Lucy and Albert moved to Chicago to get away from the racist violence and threats of the KKK. There, they joined the socialist International Workingmen’s Association, and the Knights of Labor, a radical labor union that organized all workers, regardless of race or gender. They had two children in the 1870s, one of whom died from illness at the age of eight. Lucy worked as a seamstress. Albert worked as a printer for the Chicago Times. These were incredibly difficult times for workers. The Long Depression had just begun, one of the worst, and longest, depressions in U.S. history. Jobs were scarce and wages were low. Additionally, bosses were exploiting the Contract Labor Law of 1864 to bring in immigrant workers who they could pay even less than native-born workers.

The Great Upheaval

In the summer of 1877, the railroad men of Martinsburg, West Virginia went on strike. Soon after, workers struck in Baltimore, and Pittsburgh, where they burned much of downtown to the ground. Workers halted rail traffic. Militias mutinied and fraternized with the strikers. It spread from New York to Louisiana, and west, to California. There were uprisings in several towns. Workers looted armories. Police and national guards killed at least 100 people nationwide.

Black and white workers united in New Orleans, Louisville, Galveston, and in Saint Louis, where they occupied government offices and took over management of city services. Karl Marx called it “the first uprising against the oligarchy of capital since the Civil War.” The event radicalized Lucy Parsons, who was living in Chicago, and set her on a course for a lifetime of activism and protest.

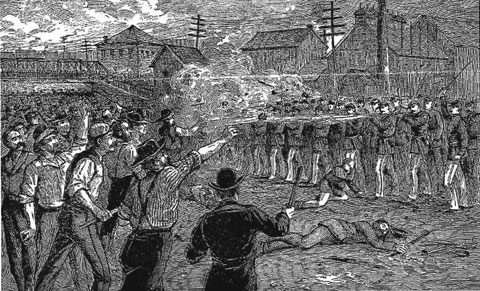

Lucy and Albert Parsons helped organize protests and strikes in Chicago during the Great Upheaval. The police violence against the workers there was intense. One journalist wrote, “The sound of clubs falling on skulls was sickening for the first minute, until one grew accustomed to it. A rioter dropped at every whack, it seemed, for the ground was covered with them.” During the Battle of the Viaduct (July 25, 1877), the police slaughtered thirty workers and injured over one hundred. Albert was fired from his job and blacklisted, because of his revolutionary street corner speeches.

Radicalization

After the Great Upheaval, they both moved away from electoral politics and began to support more radical anarchist activism. Lucy condoned political violence, self-defense against racial violence, and class struggle against religion. Along with Lizzie Swank, and others, she helped found the Chicago Working Women’s Union (WWU), which encouraged women workers to unionize and promoted the eight-hour workday.

During the late 1870s and early 1880s, she wrote numerous articles, including “Our Civilization, Is it Worth Saving?” and “The Factory Child. Their Wrongs Portrayed and Their Rescue Demanded.” In 1884, she helped edit the radical newspaper The Alarm. She wrote an article for that paper, “To Tramps, the Unemployed, the Disinherited and Miserable,” which sold of over 100,000 copies. In that article, she advocated using violence against the bosses. In 1885, she published “Dynamite! The only voice the oppressors of the people can understand,” in the Denver Labor Enquirer. During this period, Lucy gave numerous fiery speeches on the shores of Lake Michigan. Hundreds of people routinely attended. Mother Jones thought her speeches advocated too much violence. The Chicago Police Department called her “more dangerous than 1,000 rioters.”

The Haymarket Affair

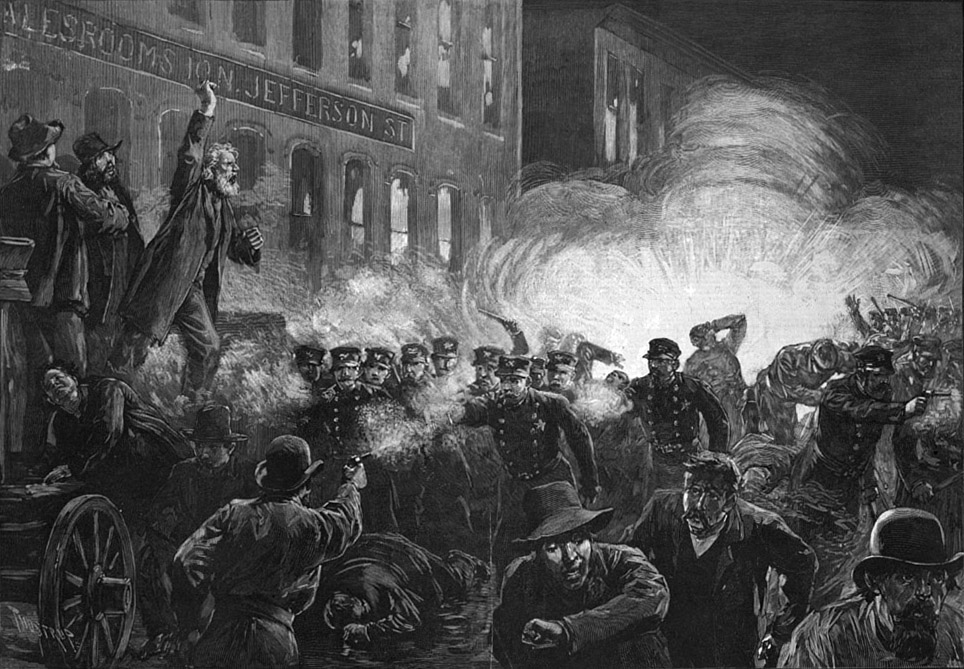

On May 1, 1886, 350,000 workers went on strike across the U.S. to demand the eight-hour workday. In Chicago, Albert and Lucy led a peaceful demonstration of 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue. It was the world’s first May Day/International Workers’ Day demonstration—an event that has been celebrated ever since, by nearly every country in the world, except for the U.S. Two days later, another anarchist, August Spies, addressed striking workers at the McCormick Reaper factory. Chicago Police and Pinkertons attacked the crowd, killing at least one person. On May 4, anarchists organized a demonstration at Haymarket Square to protest that police violence. The police ordered the protesters to disperse. Somebody threw a bomb, which killed at least one cop. The police opened fire, killing another seven workers. Six police also died, likely from “friendly fire” by other cops.

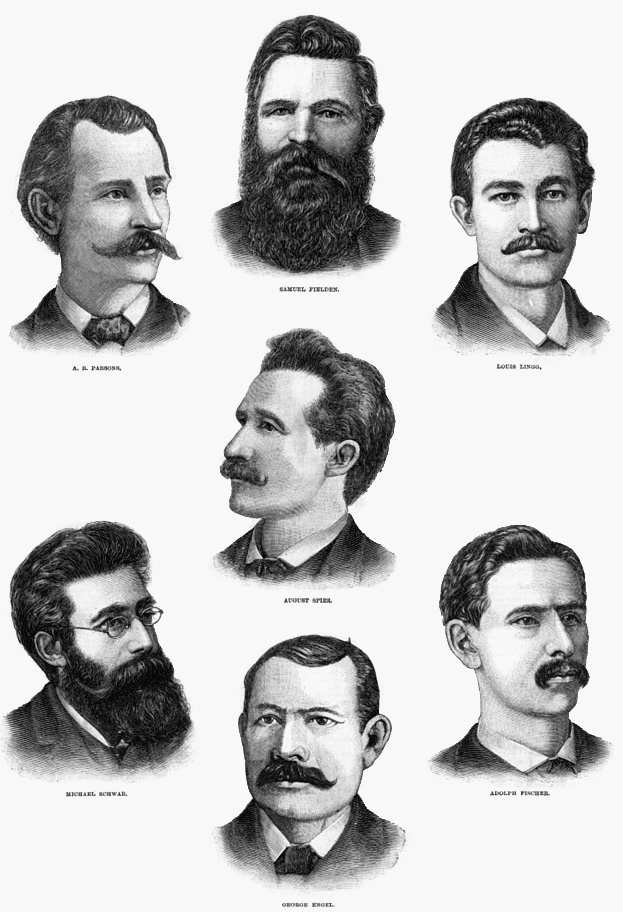

The authorities, in their outrage, went on a witch hunt, rounding up most of the city’s leading anarchists and radical labor leaders, including Albert Parsons and August Spies. Lucy toured the country, giving speeches and distributing literature about the men’s innocence. Everywhere she went, police greeted her. They often barred her from entering the meeting halls where she was scheduled to speak. They arrested her numerous times.

Organizing to Free the Anarchists

Despite her efforts, and those of other activists fighting to free the Haymarket anarchists, the courts ultimately convicted the seven men of killing the cops, even though none of them were present at Haymarket Square when the bomb was thrown. They executed four of them in 1887, including Albert Parsons. On the morning of his execution, Lucy brought their children to see him for the last time. But the police arrested her and strip-searched her for explosives. Albert’s casket was later brought to Lucy’s sewing shop, where over 10,000 people came to pay their respects. 15,000 people attended his funeral. Several years later, the governor of Illinois pardoned all seven men, determining that neither the police, nor the Pinkertons, who testified against them, were reliable witnesses.

After the Haymarket Affair

After her husband’s execution, Lucy continued her radical organizing, writing, and speeches. In October 1888, she visited London, where she met with the anarchists Peter Kropotkin and William Morris. In the 1890s, she edited and wrote for the newspaper Freedom, A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly. In 1892, Alexander Berkman (an anarchist comrade and lover of Emma Goldman) attempted to assassinate the industrialist Henry Clay Frick, for his role in the slaughter of striking steel workers, during the Homestead Strike. Lucy published the following in Freedom: “For our part we have only the greatest admiration for a hero like Berkman.”

In 1897, Lucy met Eugene Debs and Emma Goldman, both of whom she admired initially. However, she began to clash with Goldman over her advocacy of free love, which Lucy felt was degrading to women. Lucy, in spite of her fiery rhetoric, and her own extramarital affairs, liked to present herself as respectable and well-bred. She endorsed monogamy, marriage and motherhood.

Lucy opposed the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War, as did most anarchists. She criticized both U.S. imperialism and Spanish colonialism. When her son, Albert Jr., attempted to enlist during the Spanish-American war, she had him committed to the Northern Illinois State Mental Hospital, where he remained for the rest of his life, dying there in 1919 from tuberculosis.

The Industrial Workers of the World

The Russian Revolution

In 1905, Lucy cofounded the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), along with Mother Jones, Big Bill Haywood, Eugene Debs, James Connolly, and others. The IWW was, and still is, a revolutionary union, seeking not only better working conditions in the here and now, but the complete abolition of capitalism. The preamble to their constitution states, “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.” They advocate the General Strike and sabotage as two of many means to these ends.

At the founding meeting of the IWW, Lucy said that women were the slaves of slaves. “We are exploited more ruthlessly than men. Whenever wages are to be reduced the capitalist class use women to reduce them.” She called on the new union to fight for gender equality and to assess underpaid women lower union dues. She also started advocating for nonviolent protest, telling workers that instead of walking off the job, and starving, they should strike, but remain at their worksites, taking control of their bosses’ machinery and property. This was years before Gandhi started leading Indians in nonviolent protest.

The Russian Revolution

Lucy continued her radical activism from the early 1900s through the 1930s, touring the US, making speeches and selling pamphlets, while also editing the radical newspapers The Liberator (published by the IWW) and The Alarm. From 1907-1908, she worked with the IWW, in San Francisco, to organize against hunger and unemployment. In 1915, she organized and led a large hunger march in Chicago. She organized for the freedom of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, labor organizers who the authorities wrongly convicted of the 1919 San Francisco Preparedness Day bombing. She also fought for the freedom of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American teenagers who the authorities falsely convicted of raping two white women in 1931.

Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Lucy, like many radicals of her day, moved toward communism. She began working with the Communist Party in 1925, officially joining in 1939. Lucy was now blind, approaching her nineties, but still participating in May Day marches and demonstrations. She died in a house fire 1942. Police and FBI combed through the wreckage, confiscating her large library and her personal writings, and never returned them to her family. She was buried in the German Waldheim Cemetery, along with her husband, Albert, where the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument stands.

“When the prison, stake or scaffold can no longer silence the voice of the protesting minority, progress moves on a step, but not until then.” –Lucy Parsons

Pingback: Union Busting and the Pinkertons - Michael Dunn