Eddie Aikau is a legend in Hawaii, and to surfers around the world. From the mid-60s to the mid-70s he rode the biggest waves at the most dangerous breaks. However, he was also a working-class hero, saving over 500 lives as a lifeguard on Oahu’s north shore. And in 1978, he tragically sacrificed his own life to save his shipwrecked comrades.

Early Life

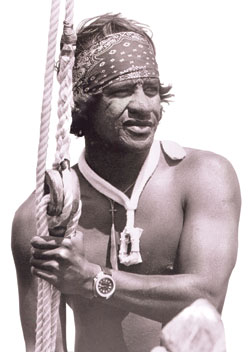

Eddie Ryon Makuahanai Aikau, born May 5, 1946, was an indigenous Hawaiian lifeguard and surfer, famous for his courage and solidarity. His Hawaiian name, Makua Hanai, means “feeding parent,” as in “one who nurtures those around him.” And he was well-known for the hospitality he showed toward friends and family, and his fearlessness as a surfer and a lifeguard.

Eddie grew up at a time when locals were not allowed near the tourist hotels and beaches in Hawaii. Racism was rife and Hawaiian culture was suppressed. Like many Native Hawaiians, his family had lost their land when the Hawaiian kingdom was overthrown in the 1890s by mainland business leaders known as the “Committee of Safety.” His family lived on a Chinese graveyard, which they cared for in exchange for free rent. Eddie left school at the age of 16 to work at the Dole pineapple cannery to help support his family.

Becoming a Lifeguard

The income from his cannery job allowed him to buy his first surfboard. Along with his brother Clyde, he began tackling the big waves of Sunset Beach and Waimea Bay. He went on to participate ten times in the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational Surfing Championship, the most prestigious surfing contest of its era. The contest was named for Native Hawaiian and five-time Olympic medalist Duke Kahanamoku. Eddie made the finals six times and won the event in 1977.

As a surfer, he was most famous for his prowess at Waimea Bay, which he surfed with the ease and casualness that others might have on a three-foot wave. In 1966, he surfed Waimea for the first time, spending six hours in the water and catching over a dozen twenty-foot waves. When the waves were 30-40 feet, he was one of the only ones riding them. There were no lifeguards in those days. Eddie and his friends often rescued tourists when they got in over their heads.

People began to take notice, including the City and County of Honolulu, which hired him in 1968 to be the first lifeguard on the North Shore of Oahu, the seven-mile stretch of world-class surf breaks that include Banzai Pipeline, Sunset Beach, Haleiwa, and Waimea Bay. During his tenure as lifeguard at Waimea Bay, not a single person lost their life, even in surf that reached 30 feet or more. This was before jet skis, when lifeguards used only fins and a surfboard. In 1971, city officials named him lifeguard of the year.

Racism

In 1972, he was invited to participate in a surf contest in Durban, South Africa. He planned to meet fellow Hawaiian surfers Bill Hamilton and Jeff Hakman at a hotel (both haoles or European-descended), but management refused to allow him entrance because of his dark skin color. The racism infuriated him. But the experience inspired him to fight harder against the prejudice Native Hawaiians experienced at home.

In the mid-1970s, the “Free Ride” generation of Australian surfers began making a name for themselves on the North Shore of Oahu. They were talented, but also arrogant, and disrespectful of the locals. This hit the Native Hawaiian surfers particularly hard, in light of the years they were denied access to their own beaches and contests.

Da Hui, a gang of local enforcers, formed in response. They beat up Australian surfer Rabbit Bartholomew, knocking out several of his teeth. They supposedly made death threats against other Aussies. Ian Cairns began traveling with a loaded shotgun. Some of the Aussies barricaded themselves in their hotel rooms.

Eddie Aikau stepped in, forming a ho’oponopono (traditional Hawaiian parlay) at the Turtle Bay Hotel, which served as a tribunal to resolve the conflict and the racism. The resolution included apologies by the Aussie surfers, and acknowledgement of the injustices and racism that persisted against Native Hawaiians. And it also led to a growing awareness in professional surfing of the indigenous roots of the sport and acknowledgement of the indigenous inhabitants of the regions where its contests are held. Today, professional surfers are identified by their national citizenship, except for those from Hawaii, who are identified as Hawaiians.

The Voyage of the Hokule’a

In 1978, the Polynesian Voyaging Society sponsored a 2,500-mile journey to re-enact the ancient route of the Polynesian migration between the Hawaiian and Tahitian island chains, using only the stars and currents as their guide. Eddie, who had become active in the renaissance of Hawaiian culture that was taking place at the time, jumped at the opportunity to join the crew on the double-hulled canoe Hōkūleʻa, a replica of the boats that first brought Polynesian settlers to the Hawaiian islands. They debarked on March 16, 1978, but the sea grew treacherous. One of the hulls developed a leak and they capsized off the island of Moloka’i.

The crew hung onto the capsized boat overnight. Neither their flares, nor radio signals, reached any rescue vessels. The next day, March 17, Eddie tried to get help by paddling the 12-15 miles to Lana’i on his surfboard. The Coast Guard eventually found the boat and rescued the rest of the crew. They launched the largest air-sea search in Hawaiian history to search for Eddie, but they never found his body. In honor of his courage and sacrifice, the state of Hawaii proclaimed March 17 to be Eddie Aikau Day.

The Eddie

The most elite big wave contest in the world is The Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational (the Eddie). They hold the contest at Eddie’s beloved Waimea Bay. However, the contest only occurs when the ocean swell will hold at 20 feet or larger for the duration of the day, with favorable winds (wave faces of 30-40 feet). Consequently, they have only run the contest ten times in its nearly 40-year history. Eddie’s brother, Clyde, won the 2nd Eddie in 1986.

During the very first Eddie, held at Sunset Beach in 1985, the waves were huge and conditions were treacherous. While the contest organizers were deliberating over whether to have the contest in these conditions, invitee Mark Foo said, “Eddie would go.” This was a reference to Eddie’s courage as a lifeguard, where he would jump into enormous and treacherous waves at Waimea Bay that no one else dared to, in order to rescue people. Soon after the first Eddie, bumper stickers started to appear throughout Hawaii with the phrase, “Eddie would go.” In 1994, Mark Foo died surfing at Mavericks, in Half Moon Bay California, about 30 minutes south of San Francisco, in surf that was 20-30 feet.